Venture Capital is a relatively small, yet highly impactful asset class. VC-backed firms comprise 63% of US market capitalization, even though only 0.31% of all incorporated businesses receive VC financing. Europe is on a similar trajectory. Despite the economic relevance of VC and the ever-growing number of highly valued private technology firms, only primitive methods are used when it comes to determining their value.

The flaws of post-money valuation

Skyrocketing valuations are the favourite subject of startup media and the general startup ecosystem. The concept most widely used to determine such valuations is post-money valuation (PMV). In PMV, the share-price paid in the most recent financing round is multiplied by the fully-diluted number of outstanding shares. This simple concept assumes that all shares of a firm are the same – which is the case in most publicly traded firms.

In VC, however, this assumption does not hold true. VC-backed firms typically exhibit a range of different share classes which are subject to varying contractual rights and may fundamentally differ in their general share type. By applying the share price of the most recent financing round to all outstanding shares, both specific structures and contractual rights are fully neglected. This can result in a substantial deviation of PMV from the fair value of a firm.

Research from Stanford shows that the PMV of US unicorns is on average 51% above what they are really worth. In this context Stanford’s Prof. Strebulaev states: “Some unicorns have made such generous promises to their preferred shareholders that their common shares are nearly worthless.” It is therefore of great importance for all stakeholders of the venture ecosystem to have a sound understanding of PMV and its limitations.

Why and when do the flaws of post-money valuation matter

The ultimate value of a firm is deterministic – it is cash and stock that can be converted into cash. PMV is nothing but a mark that reflects theoretical, unrealized gains as of a single point in time. In a positive liquidation event, protecting contractual terms do not come into effect and the proceeds are distributed according to the general ownership structure of the firm. In a negative liquidation event, however, the share structure and cash flow-related terms can have a substantial impact on the distribution of the proceeds.

This is particularly relevant for founders, as the securities they usually hold, common shares, do not have any form of downside protection. Considering that investors pay a share price that incorporates a downside protection, this price naturally overstates the value of common shares without such protection. By using PMV, common shareholders tend to have a blurred understanding of their personal wealth associated with the shares they hold.

The same thing goes for investors. Investors who mark their investments based on PMV falsely assess their performance and communicate this performance mark to their limited partners, misleading their comprehension of risk exposure. Therefore, shareholders should assign a distinctive value to every different share class they hold, depending on the contractual rights associated with it. They should also be aware that owning a part of a company is not a static thing, but fluid with a number of factors that can change the overall ownership equation over time.

How to do better than PMV

First and foremost, founders, investors and all other stakeholders of the venture ecosystem should have a reasonable understanding of equity types and contractual rights. There are excellent resources that provide an overview of deal terms and valuation – from rather fundamental concepts to more advanced content. When the basics are well understood, shareholders should analyze the share structure of their firm to model the conversion points of the different share classes and derive the payoff structure.

To illustrate how important it is to understand the payoff structure, consider the following payoff diagram: On the x-axis, the liquidation value of the firm is displayed (Company exit value). The y-axis exhibits the payoff a share class is entitled to, conditioned by the company exit value. Herewith, it becomes obvious why it is crucial to consider the specifics of different share classes.

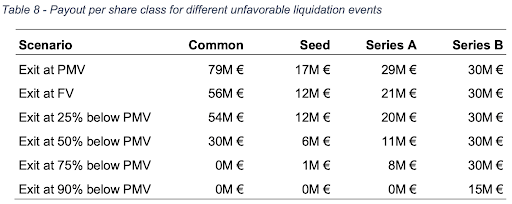

The following simulation impressively illustrates how powerful a simple downside protection with a 1x liquidation preference, that is subject to a senior claim, can have. In “down exits” (exits below the PMV of the latest financing round), the most recent investors always assert their senior claim, which shifts value from other equity holders to them. For example, in an exit event 90% below PMV, Series B investors still recover 50% of their investment, while all other investors receive nothing.

Information like this provides valuable insights for all shareholding parties of a firm. VC firms gain a more profound understanding about the value, and therefore also about the performance of their investments. VCs, founders and other shareholders must conduct scenario analysis that helps practitioners to pursue more informed decisions during periods of uncertainty within a firm. It allows founders and investors to negotiate deal terms on a sound basis, by having a clear understanding of the impact that each term has on share value. The same is true for all common stockholders, founders and employees.

Applying more sophisticated analysis would allow all shareholders to evaluate their private wealth and their risk exposure more precisely. The figures shown above display the pressure equity financing rounds put on the payoff values of common equity holders. Specific numbers like this help founders and employees assess their financial plans and the performance pressure resting on the shoulders of their firm much clearer.